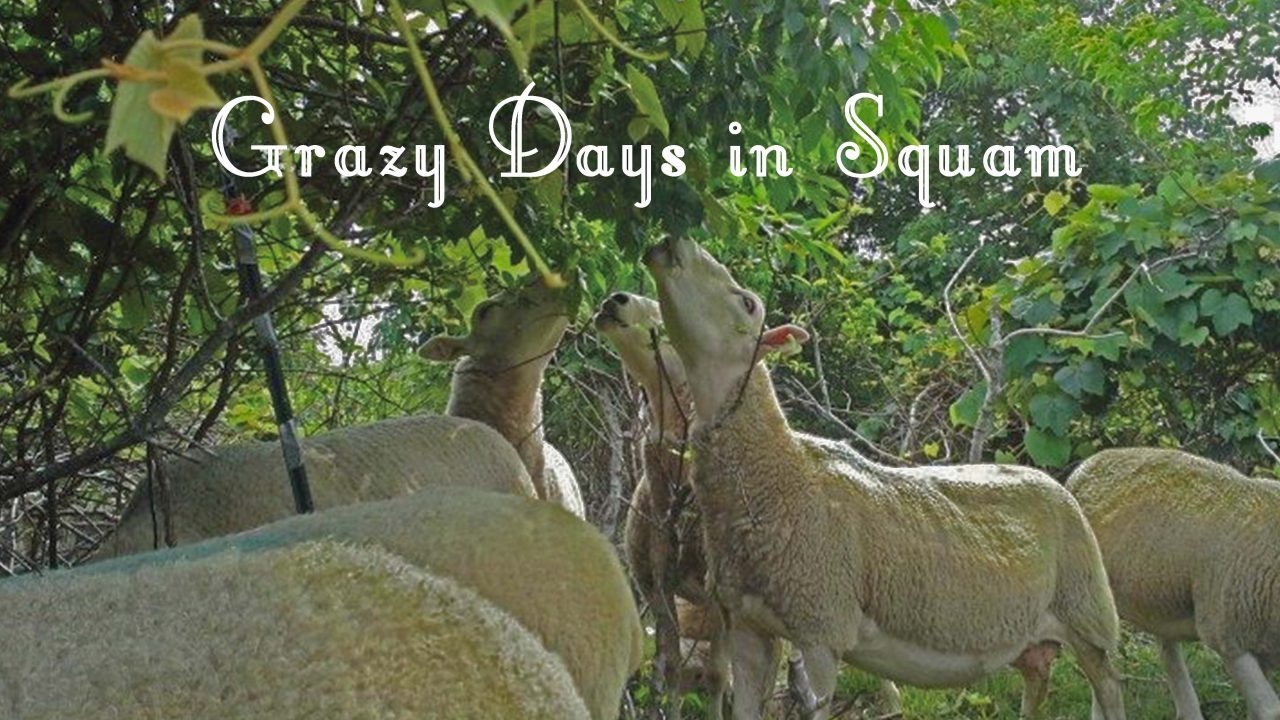

Grazy Days in Squam

by Karyad Hallam

Photos courtesy of Nantucket Conservation Foundation

The Sheep Grazing Program started in 2005 by the Science Department at the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, led by then director Karen Beattie. Jessica Pykosz was the livestock manager and cared for the herd daily, along with her border collie, Rem. The Sheep Grazing Program is no longer active but this article provides an informative overview of this very fascinating study of landscape and livestock on Nantucket.

In Sonoma, California, there is a family-owned vineyard called Cline Cellars that implements an all-natural weeding mechanism called “woolly weeders.” These weeders not only root out virtually all weeds that would otherwise steal water and other precious resources from the grapevines (which are secured well above the weeders’ reach), but also fertilize the ground and earn a 100% organic rating. The woolly weeders, of course, are California sheep.

For a long time, Nantucket sheep took care of the land in much the same way. In fact, when the first European settlers came to the Island, sheep were right there with them, most likely Cotswold sheep, named after that region of English countryside and popular with American farmers of the time. With no coyotes, wolves or natural predators to hold them back from busily cutting down dense plant growth, these sheep are most likely the main cause for why the island looks the way it does today. They changed the habitat mosaic, making room for plants that can thrive only in sandplain grassland and heathland environments.

However, in the 1800s these four-legged landscapers went into decline, and plant growth went unhindered. Taller trees and vines crowded the open spaces and forests hogged up light and resources. In 2005, the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, which has successfully acquired and protected 8,990 acres of Nantucket land, decided to try something new – and very

hungry – to fight this encroaching overgrowth.

The Sheep Grazing Program was started in 2005, by the Science Department at the NCF, led by then director Karen Beattie. The project set out to gather valuable data, and relied entirely on donations from community members and conservators for equipment, personnel and feed. Originally, the project was intended to be a one-season experiment, using 48-50 head of Cotswold sheep to see what plants the sheep would eat, what plants the sheep would not eat and what effect this would have on the landscape.

In the springtime, the ewes were brought in to graze, and they brought not only their appetites but some unexpected bundles of woolly joy. “Apparently,” observes Beattie, “at one point, unbeknownst to both the breeder and us, a ram must have hopped the fence at the off-island farm where they came from. We had no idea. So one day we went out, and there were lambs!” Yes, it really was that unexpected.

The rest of the herd was returned to the breeder, but since the lineage of the lambs could not be verified, they had nowhere to go. So the Foundation decided to keep the seven ewes and their lambs, and the team’s very first native herd was born. Raised on island foliage and feed, the new herd could eat even the tough stuff left untouched by their picky lawn-nibbling forebears.

Some of the plants that they munch on: scrub oak, poison ivy and grape vines. Scrub oak, it should be noted, is not an invasive species; it actually does belong in the sandplain grasslands. However, the important thing is to keep its numbers low, so it does not out-compete other plants.

The herd, currently numbering 112, was composed of mostly females and neutered males – only three rams at a time were kept for breeding. It was the first time since 1949 that Nantucket had a sheep herd of more than 100. Since the project’s inception, the breed of choice had switched from the historical Cotswold to North Country Cheviot crosses. They could be seen wandering on Squam Farm throughout the year, taking shelter from the winter winds in their permanent pasture. Wind shelter is all they need; their wool is quite warm, even in temperatures below freezing.

In the springtime, the sheep would leave the permanent pasture to roam across the 210-acre Squam Farm property. Known as “The Wrecking Crew,” they not only destroyed excess flora but also helped to rehabilitate terrain that needs more cover by spreading seeds on their wool and “pollinating” certain areas. They were rotated every couple of days from acre to acre within the perimeter of a portable electric fence. This ever-shifting perimeter was carefully moved under the supervision of livestock manager Jessica Pykosz and her border collie sheepdog, Rem.

“over 80 percent of the worldwide acreage of sandplain grasslands occur on Nantucket, Tuckernuck and Martha’s Vineyard.”

To move the sheep from point A to point B involved first setting up the new fence, then moving the sheep from the old enclosure to the new one. Rem, a former national qualifier, and the herd knew what to do with these routine moves, but at any time Pykosz could use precise signals (sometimes whistling, mostly verbal calls) to tell the sheepdog to slow down, speed up, back up, lie down or move clockwise or counterclockwise. (Rem rarely needed to be told to speed up though – it seemed he was constantly trying to beat his own record.)

Pykosz, who was with the program for about five years, was responsible for the day-to-day care of the flock. She grew up on farms learning about livestock, so she was quite at home in the field. “I’m a very lucky farmer,” she said. “Not everybody on Nantucket gets the chance to use 40 acres of land.”

She monitored all aspects of her flock’s health from their teeth to their stress level, helped deliver the babies when needed, protected the herd from parasites and viruses and adjusted their diet – for example, adding in more young scrub oak to boost protein, or older grape vines if they needed more fiber and tannins. She was proud to report that all her charges became healthy, self-sufficient and excellent mothers. Of the 53 lambs born that year, only one had to be bottle-fed.

The crew did a good job. If one walked through Squam Farm’s trails, the line between grazed and ungrazed areas is very clear. However, the job had its challenges as one gets to know the land. “Every year, they always find something new to throw at me,” she said. For example, that one lamb that had to be bottle-fed was a first. Normally baby sheep grow their teeth within a week, but in the case of this lamb, dubbed “Sharkface,” he was born with his teeth. It took a while to figure out why his mom would run away from him after only nursing him for a few days. Now Sharkface, who became closely acquainted with humans from an early age when he was bottlefed, served as an ambassador to those who would take a tour of the farm, even enjoying the occasional scratch.

The team hoped that the sheep will take to new plants like huckleberry and bayberry, but so far they remain an acquired taste – their aromatic oils have a little too much zest. Also vying for space are honeysuckle (an invasive woody shrub) and fox grape vine. It is natural for forests of white oak, red maple and pitch pine to grow out in the moors, but too much cover can easily throw off the delicate balance.

The process of plant succession is continuously reset in Nantucket’s grasslands and heathlands, using three different methods that the researchers often change around to maximize results: sheep grazing, controlled burning and brush cutting. It is important to monitor the process closely, as the sandplain grassland is a habitat unique not only to Nantucket, but also to North America and the world. According to the Nantucket Conservation Foundation’s web entry on habitat types, it is estimated that “over 80 percent of the worldwide acreage of sandplain grasslands occur on Nantucket, Tuckernuck and Martha’s Vineyard.”

These meadows on the moors are home to ox-eye daisy, yarrow, milkweed, sandplain gerardia, purple milkweed, bushy rockrose and pasture thistle. Endangered species that benefit directly from the sheep grazing include: the New England blazing star (its narrow, numerous round blooms pop up late in the season, around September/October); the modest yellow petals of the bushy rockrose; the tufted purple needlegrass; the fernlike St. Andrew’s cross and sandplain blue-eyed grass (not a grass but a member of the iris family, sporting small violet-blue flowers with bright yellow-orange centers). Not only do sheep reduce the brush cover, giving these species precious sunlight, but their hooves trample the ground, churning up the layers to leave bald patches where the seeds of these rare flowers can germinate. In the wake of these woolly weeders, new life begins.

So, as you can see, this herd of sheep created a nostalgic scene.

Article edited. Full version available in ONLY NANTUCKET Fall 2014.