Boston & Nantucket Pops – How it Began

By Jack Thomas

Sitting in his office in Boston’s Back Bay, overlooking a panorama of treasured symbols like Beacon Hill, the Public Garden, and the golden dome of the State House, now shimmering in the springtime sun. David Mugar, 79, patriarch of one of Boston’s most charitable and influential families, is responding politely and modestly to questions about his family’s charity and perhaps his most significant personal contribution — his support for 43 years, physically and financially, of the Boston Pops July Fourth concert at the Hatch Shell. This concert has enraptured as many as 700,000 spectators into a patriotic fervor during the grand finale, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, which is accompanied by a rootin’- tootin’, flag-waving, cannon firing, bells-a-ringing, eyes-a-popping, flamboyance of fireworks.

Rootin’ – tootin’, flag-waving, cannon firing, bells-a-ringing, eyes-a popping, flamboyance of fireworks

So successful has been the Boston concert that it spawned a spin-off, in Nantucket, which adopted the idea 22 years ago, and then fine-tuned it for Nantucket’s individual character. When founder, Kathryn Clauss, called Mugar for counsel, among the questions she posed was how Mugar had found a place to buy fireworks. “I told her that I just looked up “fireworks” in the yellow pages,” Mugar recalled, referring to a telephone directory, printed on yellow pages that organizes businesses by product.

The August concert on Nantucket draws more than 7000 people to Jetties Beach. General admission is $30, but for those desirous of listening to the concert while enjoying a gourmet dinner on the beach, a table for 12 can be purchased for up to $50,000. Every year, proceeds of about $2 million go to Nantucket Cottage Hospital.

Dr. Margot Hartmann, chief executive of Nantucket Cottage Hospital, acknowledges what the concert does for the island. “The Boston Pops on Nantucket has become a tradition and one that provides our hospital with an indispensable source of support … our biggest fundraiser of the year, every year.”

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, just as Boston’s July Fourth celebration came to symbolize a renewed allegiance to America, so, too, the narrative of three generations of the Mugar family symbolizes the dreams of many newcomers to America — a pathway from immigrant to citizen, poverty to wealth, anonymity to luminary.

The story of the Mugar family begins with the arrival of a six-year-old boy, Stephen Mugar, whose family fled Turkish oppression in 1906, and after the long voyage, arrived in New York Harbor. The day was so poignant that little Stephen never forgot gliding past the Statue of Liberty, never forgot setting foot on his new homeland at Ellis Island, and never forgot the gratitude he felt and the pledge he made, despite his youth that he would work hard to repay America for welcoming his family.

It is a debt Stephen and his family has paid back many times, by heart, humanity, and hard work, not to mention the many millions of dollars they have contributed to the arts, education, health care, hospitals, libraries, scholarships, patriotic events, and other enhancements to American culture.

It was a different country in 1906 that welcomed Stephen Mugar. Teddy Roosevelt was President. The Indian Wars had ended a mere 15 years earlier with defeat of the Sioux at Wounded Knee. Most of San Francisco was destroyed that year by an earthquake. The Wright Brothers were granted a patent for the first airplane. Oklahoma became the 46th state. The first radio program was broadcast. Moving pictures were a curiosity; hot dogs were introduced at the Polo Grounds. Americans were dancing to Waltz Me Around Again, Willie.

Upon arrival in America, young Stephen rolled up his sleeves and went to work, first selling newspapers, then sweeping out his dad’s grocery store in Watertown, and finally building the family business into a blockbuster enterprise so that, by the time he sold it in 1964, the business included 35 Star Markets and 70 Brigham’s ice cream shops.

At sixty-three years old, Stephen celebrated by giving $1 million towards a new library at Boston University. The pledge he had made upon arrival in his new country so many years earlier, no doubt was on his mind at the dedication. “Coming to America from Armenia,” he said, “I have never taken for granted all the wonderful things this country has to offer.”

Dressed in a blue-plaid, button-down shirt and bright red suspenders, his son, David Mugar is eager to talk about his own, conspicuous legacy to Boston — and indirectly to Nantucket — the Boston Pops July Fourth concerts that were suffering from dwindling audiences until 1973, when Mugar became executive producer and inspired a revitalization of the concerts, including the introduction of fireworks. In the interim, the concerts have attracted 17 million people to the Esplanade and many millions more on national television, all in celebration of the America to which his father had pledged fidelity 113 years ago.

Crowd on the grass of the Esplanade, after securing their spot many hours before the concert begins

The Hatch Shell in all its glory on the Fourth of July!

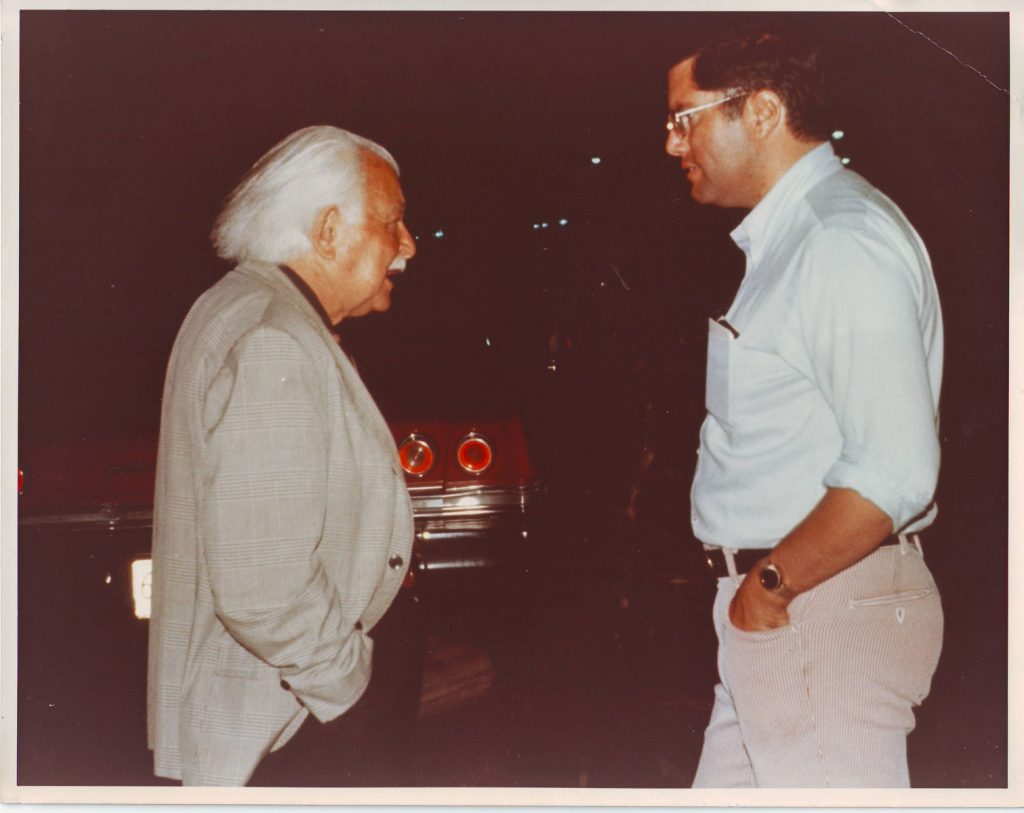

Famed conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler and David Mugar

Current day conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra

Neil Diamond performig in Boston at the Hatch Shell

A choir performs with the Boston Pops

The beginning of a July Fourth concert

End of the Boston Pops concert during the 1812 Overture amongst a shower of confetti!

The idea to reinvigorate the concert grew out of an implausible conversation. Here’s what happened.

David was a “spark,” a euphemism that describes someone whose car is equipped with police and fire radios and who scouts the city for fires and other disasters. David was good at it, sometimes arriving before firefighters, and his photographs won global awards. He was a friend to another spark, Arthur Fiedler, then 78 and conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra for 43 years. Some nights, David would pick up the maestro at his home on Hyslop Road in Brookline, and from 10 to three or four in the morning, they’d drive around the city or park in Kenmore Square to wait for a police or fire call of interest.

In late August 1973, the two men left a coffee shop in Kenmore Square after midnight, and as David piloted his black Chevrolet along Commonwealth towards town, he brought up a delicate subject. Although the Pops regularly sold out Symphony Hall, audiences had dwindled at the free concerts at the Hatch Shell.

Mugar began diplomatically: “Mr. Fiedler, I’ve had this idea for some time, and it’s yours to say yes or no. What do you think if, next July Fourth, you end the concert with the 1812 Overture, and I’ll try to find some actual cannons and we can arrange for a lot of church bells to ring across the Back Bay and Beacon Hill, and real fireworks at the end. What do you think?” Fiedler was stunned. ”Geez,” he said, “that would be terrific, David. Why don’t we let all hell break loose?”

The following summer, 1974, lured by a revived concert and kaleidoscopic fireworks, the audience tripled to 75,000. Spectators blanketed the grass of the Esplanade and lined the Charles River, and as they watched from boats on the water and homes on Beacon Hill and the Back Bay, Fiedler led the Pops in the 1812 Overture. With the crowd on its feet, cheering, and waving American flags, Mugar’s production let loose with cannon fire, deafening aerial explosions, the amplified peal of bells from Church of the Advent, and from a barge in the river, a 20-minute volley of cacophonous fireworks that culminated in a glowing red, white, and blue salute that illuminated Boston for miles.

“Well, I don’t know much about music,” says Mugar, “but I saw it as a bombastic piece, and what other music has church bells and cannons and avails itself so well of fireworks?”

Well, I don’t know much about music,” says Mugar, “but I saw it as a bombastic piece, and what other music has church bells and cannons and avails itself so well of fireworks?

In 2016, after 43 years as executive producer, Mugar announced his retirement, and responsibility for production of the concert shifted to the Pops. Then, last month, while vacationing in Florida, Mugar received a telephone call from Mark Volpe, managing director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, of which the Pops is adjunct, and he asked if Mugar could return to Boston and provide guidance about the budget. Right away, Mugar booked a flight home. “I’m happy to help save this thing,” he said. “It’s my baby.”

At a recent meeting, he proposed a way to save money. Tugboats and barges involved in launching the fireworks cost about $500,000, and if the details could be worked out, perhaps the launch pad could be moved to a land site – possibly the Massachusetts Avenue bridge over the Charles, for example – and that might save as much as a quarter of a million dollars.

Moored boats off the shore of Jetties Beach, Nantucket

Crowds for the Nantucket Pops concert

Keith Lockhart assumed the post of principal Pops conductor in 1995

Nantucket Pops production

TV personality, Katie Couric and guests on Nantucket

Although his business enterprises are too capacious to be listed here, over the decades, as founder and CEO of Mugar Enterprises, David has developed and managed commercial real estate, including hotels, malls, shopping centers, offices, labs, and industrial space. In 1996, he founded Brownfields Recovery Corp. to redevelop environmentally impacted properties that include St. Croix Renaissance Park on the 1300-acre site of the former Alcoa plant in the Virgin Islands. In partnership with Don Law, they own Boston House of Blues, Brighton Music Hall, Paradise Nightclub, Orpheum Theatre, and the Boston Opera House, which hosts Broadway shows and the Boston Ballet. He was one of four developers of Boston’s luxury, five-star hotel, the Mandarin Oriental on Boylston Street. In addition, he oversees equity and bond investments, retail businesses, venture capital, and other enterprises. After a 13-year fight before the Federal Communications Commission, which the Supreme Court ultimately decided, he won control of the license for Boston’s Channel 7 and an affiliated radio station and served as CEO from 1982 to 1993.

As if that were not enough to satisfy the Mugar pledge of allegiance to America, Stephen contributed millions of dollars in scholarship and buildings on such campuses as Boston University, Suffolk University, Colby-Sawyer College, Boston College, Brandeis University, Tufts University, Northeastern University, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

David continues the family’s generosity, financing construction of the Museum of Science’s Omni Theater, named for his parents and patronized in the past 25 years by more than 17 million visitors. In addition, to the July Fourth concert, the Mugar family has, since 1999, promoted and financed New Year’s Eve fireworks on Boston Common. In 2001, David donated $10 million to Cape Cod Hospital for construction of a four-story patient-care facility. In 2012, he formed the Mugar Foundation, which will be generously endowed upon his death, and, among other missions, will recognize random acts of kindness. There are many more, from the Armenian Museum in Watertown to the Mugar Center for the Performing Arts at the Cambridge School of Weston.

Fourth of July

In his will, Mugar has arranged for the fireworks to play a role even after his death. His body will be cremated. Half the ashes will be buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery alongside his parents, and on the July Fourth following his death, his remaining ashes will be enclosed in a capsule and shot off by fireworks into the sky above the Esplanade. “And I’ve already paid for it by credit card,” said Mugar, ever the businessman. “That way, I get the points now, while I’m alive.”

Article edited. Full version available in ONLY NANTUCKET SUMMER 2018.