A Boat for All Seasons

By Charles P. Ade

Like a subtle work of art, the lines of a dory are both elegant and simple. They exhibit the craftsmanship of the boatbuilder who has created a beautiful sculpture of grace and utility. Indeed, what was originally conceived as a working boat designed for fishing from the shore and also, in a later variation, from a mother ship, has evolved into one of the more popular recreational craft ever built while still retaining its workmanlike pedigree and flowing lines. But what exactly is a dory?

Its roots go back to Europe but its legacy, at least here in New England, goes back to 1793 to Simeon Lowell’s Boat Shop, now a National Historic Landmark and still building dories, which began operations on the banks of the Merrimack River in Amesbury, MA, with a design later called a “Swampscott” dory. While owing much to the English “wherry” (a long, smooth-sided boat with a flat bottom in the middle), this dory has rounded sides and is clinker built (hull planks overlap each other; also called “lapstrake”). It, too, has a flat bottom, and not having a keel made it a very stable vessel that could be launched from the shore, usually with a crew of two. The rounded sides afforded greater buoyancy and the raked ends enabled this dory to be launched into the surf; thus, the more generic term of “surf dories” arose which accounted for many variations of this style.

Its roots go back to Europe but its legacy, at least here in New England, goes back to 1793 to Simeon Lowell’s Boat Shop,

. . . on the banks of the Merrimack River in Amesbury, MA . . .

As the fishing industry began to increase in demand and volume, it saw the use of larger ships sailing further out to haul in greater catches via dory-trawling. In the early 19th century, Lowell’s Boat Shop began to design and mass-produce a dory with straight, higher sides and a deeper draft that could hold a sizable catch itself and could be easily stacked on the deck of the mother ship. The ability to mass-produce such a boat was a significant advance in manufacturing for the then burgeoning fishing industry in the new nation. Called the “Banks” dory for the fishing grounds that it would ply, it would become the staple of fishing fleets on both coasts.

Toilers of the “Sea Five” surf fishermen carrying a dory in from the ocean (circa 1880s)

Easy Street boat basin and Steamboat Wharf, with the paddle steamship “Nantucket” inbound

A fisherman in a dory, landing on the beach

(circa 1890s)

Fishing dories on the beach at Surfside (circa 1890s)

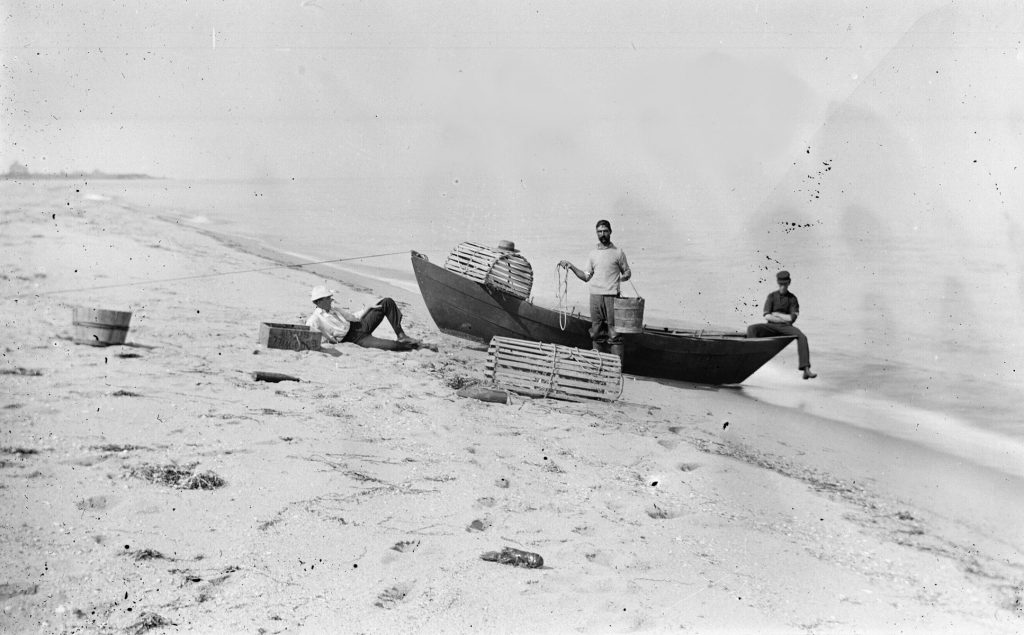

Three lobster fishermen with their lobster traps and dory on a beach (circa 1880s)

photos courtesy of Nantucket Historical Association

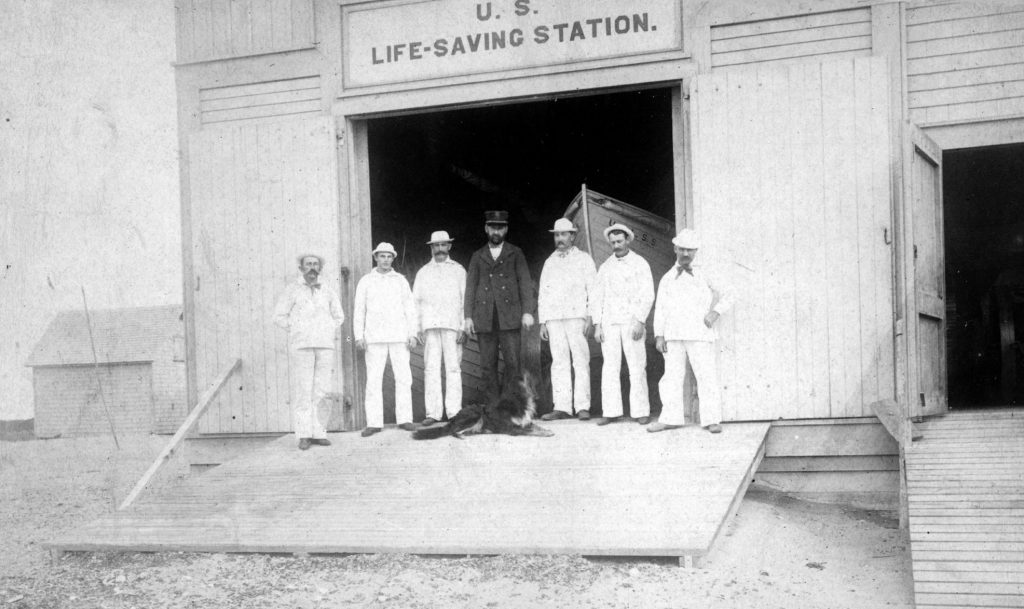

With the whaling industry at its peak on Nantucket in the early to mid-1800s, there were not a lot of dories plying the waters offshore for commercial fishing, but rather for individual sustenance and other needs. It was still a utilitarian workboat that could be launched from the shore into the sea or ply the inner harbor. It was not uncommon to see dorymen scalloping, eel fishing, or setting their lobster traps as well. But there arose a need for a boat that could be launched from the shore to rescue crew and passengers of sailing vessels stranded just offshore where other sailing vessels couldn’t risk aiding in assistance. With the establishment of the first volunteer life-saving station in Cohasset, MA, by the Massachusetts Humane Society in 1807, this need was answered with the first “lifeboat” which was a large surf dory of 23-26 feet in length that could be manned by upwards of four to seven men. Because of their size, these lifeboats were carted on carriages, which could be wheeled to the site of where a ship was foundering and then launched. On Nantucket, at one point, there were four life-saving stations because of the surrounding shoals and sandbars – at Coskata (near the site of the present day Egan Maritime Nantucket Shipwreck and Life-Saving Museum), Surfside, Madaket, and Muskeget. Officially, the U.S. Life-Saving Service (USLSS) was created in 1871 as a government service to formally address rescues on the coasts and Great Lakes, and for many years the Humane Society, which at that point had 78 boats and 92 stations, co-existed with them; the USLSS and the Revenue Cutter Service were later merged in 1915 to create the United States Coast Guard.

Coskata Life Saving station and crew, keeper Walter Chase in the center (circa 1890s)

The Surfside Life Saving Station, with two equipment carts out front. This station later became a youth hostel (circa 1905)

The Surfside Saving Station, with two boats on wheeled cradles. One of the boats is being repositioned by the crew (circa 1910)

Photographic postcard image of reflections in the harbor water of a sloop and dory tied together at the dock of Old South Wharf, Nantucket. Unitarian Church clocktower in the background (circa 1880s) – H.Marshall Gardiner post card

A dory tied at the shore in a tidal creek in Quaise (circa 1960)

photos courtesy of Nantucket Historical Association

During this time, the dory was undergoing various iterations based on needs and the creativity of the boatbuilders. Sailing rigs were incorporated early on as a means of exploring further offshore as fishing stocks were depleted, but sailing as a recreational pursuit was beginning to be appreciated more and more. The beauty and symmetry of its lines as well as its ease of handling and relatively low-cost made the Swampscott-style dory a favorite. A jib sail, forward of a mast that was mounted towards the bow, and the triangular mainsail were typical of what were known as Beachcomber and Alpha dories in the early 1900s, which also featured a rudder and removable centerboard. The sailing dory could now be seen as a “racing” dory. Soon there were different sail rigs such as the sprit rig, or spritsail, a four-sided sail that is laced to the mast and supported at its peak diagonally by the sprit or spar. Other uniquely named rigs such as the “leg of mutton” spritsail, which uses the familiar triangular sail, and the “cat” rig, which is the basic triangular sail supported by the mast and a single sprit boom in the well-known “catboats”, also appeared. Decking started to appear on some of the sailing dories leaving a cockpit for the helmsman as these boats became more sophisticated. And the “tombstone” transom of the Swampscott dory was widened to accommodate an outboard engine to further enhance its versatility. The working boat had evolved into a recreational craft.

Erastus Chapel, in his summer lifesaving uniform, with his dory at North Pond, on Tuckernuck (circa 1910)

Erastus Chapel’s Model-A Ford being transported to Tuckernuck on two dories to be used by his family members. Charles Glidden on hood of vehicle. Erastus was the grandfather of Ruth Chapel, who later married and was known by many on Nantucket as Ruth Greider (circa 1930s)

photos courtesy of Nantucket Historical Association

The dory has truly represented the evolution of a boat. Tracing its lineage to the bateaux and wherries of France and England, respectively, the classic and unadorned Swampscott dory, and its utilitarian cousin, the Banks dory, have transcended from their original role as strictly workboats to craft that provide recreational as well as race sailing. From fishing, scalloping, and lobstering to sea rescues, the dory has served admirably in its many roles, even as a car transport to Tuckernuck!

a spirit rigged dory for summer enjoyment

And today, during the winter holiday season, the Killen Christmas dory in the Easy Street Boat Basin reminds us that it also carries goodwill to all.

Dory first placed in 1965 by Sidney Killen